December 17th, 2019 by admin

On Thursday 29 September 2016 the annual black tie dinner was held at the Caledonian Club.

The dinner did not follow the usual format as there was a raffle and a cheating quiz. These raised £800 which has been donated to MacMillan Cancer and Chrohns and Colitis charities.

There were six quiz teams who were unscrupulous and absolutely engaging in their desire to win and aid charity – in the end the Blue team gained the lead by stealing a massive 100 points from other teams by pledging £100 to charity! This left one team with a negative score (and a huge smile in spite of it) at the part they had played in raising such a large amount for well-deserved causes.

A big thank you to all members and guests who supported the event and in particular to David Wood, our secretary for his year-long organisation, Dr Alan Sherratt for the preparation of the table menus, Paul Kingston for undertaking the raffle, Chris Jones for being our photographer on the evening and of course the sponsors. Also thank the Caledonian Club for wonderful hosting, lovely food and attentive service.

We’ve reproduced the toast to the Rumford Club below delivered by Chris Jones:

Here’s my anecdote. Looking forward to meeting my wife at the station, the car was immediately recognisable, even without glasses.

I enjoy any debate about our industry. Anywhere. But my regular critique seemed unusually out of place. Still stationary, I collected myself:

“Our car isn’t an automatic – and you are not my wife!”

To prevent re-occurrence, I joined the Rumford Club.

And tonight we celebrate the eve of the Club’s 70th year.

At the Club’s inauguration, it was a time for rebuilding – purposeful. Excess capacity and technological advances in building services held great potential. But the Club’s very first question was noticeably reflective:

“…Is air conditioning as practised in 1947 a menace or a benefit to mankind?”

We are now in an era of record-breaking temperatures, abrupt change and more frequent weather events. Reflections and the future of building services engineering still need the Rumford Club. Part of its growing intellect resides in ethics, societal outcomes and shared values.

But for sustaining the Club, we applaud the hard work of volunteers on the committees.

Of course, some members and contributors are no longer with us. We pause to appreciate them.

I was asked to suggest how this marvellous invention has flourished.

We do know that buildings are getting more complex. Research shows that complex systems develop through trial and error. So let’s add that Rumford is a safe environment in which to inquire, debate, change our minds and even admit uncertainty.

We also know that Rumford is about dining with conviviality. But it’s more than a place to share knowledge, experience, the earth’s rich harvest and to listen to captivating speakers.

Each dinner is unique, like kaleidoscope images. Colourful members and guests, a comb of cells, a hive of rich, germane conversation. Just look around you tonight…

Whether we are in our twenties like Jack Wardale or our nineties like Noel, we are here in our personal capacities. Rumford is not bound to any particular institution. There are no ranks or evaluation.

Like modern science, Rumford sees no bounds in standardisation or uniformity. The Club delights in variability.

Rumford has also adapted. Thirty years after the Lady Chatterley ruling challenged so many perceptions, the Club admitted its first woman member – in fact our current chair.

Industry demographics, perhaps – there are some traditions in Rumford, but we also celebrate social progress.

Rumford is diverse. Designers, members in craft, construction, education, technical sales, they join other environment disciplines, and of course many welcome guests.

It’s well adjusted. Rumford’s personality shares interest, empathy, sometimes candour: but it always greets ideas and human values with patience and respect.

In Rumford, anyone is welcome to dine by our side. Summing up the true vitality of human nature, I hope that these glowing exchanges will always be our shining moments.

That’s all I have.

“…To another seventy years of warmth and intellect, understanding, acceptance, respect and even forgiveness, which delight us in the Rumford Club.”

December 17th, 2019 by admin

Fiona Cousins (Arup) and Julia Evans (BSRIA) led the debate, which was facilitated by Rod Bunn of BSRIA.

The opportunity of IPCs

Rod put up a slide with some initial thoughts. Could IPCs:

- Provide greater efficiency and performance?

- Provide a greater focus on customers’ needs?

- Enable an end to lowest tender selection?

- Allow greater demand for demonstration of competency and quality control by contractors?

- Provide metrics for measuring resources and the tenderer’s ability to perform?

But might they make contract wording even more of a black art and lead to more work for expert eye-witnesses?

IPCs are a development of existing contractual practices

Fiona argued that such kinds of contracts should indeed be the norm.

Most contracts have the purpose of sharing risk while working towards a specific outcome. The traditional contract normally prescribes what should happen if the outcome is not achieved, but if there is an upside to the outcome, then shouldn’t this be incentivised? This notion is the root of the advantage for IPCs.

The current contractual situation does not really favour anything other than achieving a satisfactory outcome. With the challenge of climate change should we not be encouraged to aim higher?

She illustrated this with an example that is a contract to save energy in an existing building, where 10% energy savings compared to the baseline might be satisfactory, but 15% or even 20% would be far better. This kind of work could be contracted through:

1) A standard fee contract

2) A performance-based contract that pays base fees without profit for a certified 10% saving with a bonus share for better savings as measured at the end of the first year

3) A contract entirely based on energy savings.

She analysed which of these contracts is likely to deliver the best long-term outcome:

With 1), standard fees tend to get driven down, so the tendency will be to do the minimum: 10% saving target achieves 10% saving, without too much revolutionary thought and the minimum of innovation, which tends to be interpreted by all parties as risk (and so to be avoided).

With 2), the contractor would indeed be incentivised to look for some innovative solutions in order to improve their cashflow.

With 3), the best result can be achieved. From the owner’s point of view the contracting is more straightforward, with one delivery contract and one place to apportion risk.

How might an IPC work?

An IPC has several levels: the contractor raises the money to do the work, hires a consultant to do the analysis and design, hires sub-contractors to do the installation, and ensures that there is a robust, agreed way to measure the results. All parties serving the client have to work together closely: their goals have to be aligned and their rewards linked and apportioned to the risks that they have to carry.

With an existing building the achievement of performance is easy to measure, but we should also be able to do this for a new building as well.

The issue remains that a move to IPCs would represent a huge sea-change in practices, for which there is little background of interpretation through case law, and 2020 is only three years away. On the other hand IPCs are a development of existing contract methods. Since we urgently need to achieve better results, we should move towards these kinds of contracts by 2020.

Hurdles to the implementation of IPCs

Julia did not disparage the potential benefits of IPCs but thought that the organisational hurdles were enormous. People, not technology, are the problem!

She illustrated the difficulties of multi-disciplinary groups coming together to achieve common goals by reference to the groupthink that crept in prior to the Challenger spaceship disaster. It’s tough to work in a group and to agree common goals, especially if people work in different organisations and with differing cultures – and why share knowledge if it is the source of your income?

There are other obstacles, which include:

1) Clients do not understand the risks

2) Fragmented procurement within the build process

3) Adversarial procurement practices

4) The need for greater specialism in a complex world and an absence of a body of knowledge and/or Codes of Practice in many areas

5) We are not prepared to invest in training people to be able to work in this way

6) The construction process means that people disperse at the end of the project, so the accumulated knowledge is lost.

Comments from the floor

Some debaters thought that there were solutions to all the above issues, and that IPC-type arrangements had already proven themselves on projects such as the Riverside School in Newcastle, but it was accepted that these were rare instances.

There remained some optimism: clients are dissatisfied with current practices and many gains were to be had if the professions worked more closely together. We should look to a more holistic education of our people, for example embodied in the Architectural Engineering degree found in Denmark, which might encourage people to understand all aspects of the process.

Our next meetings

The Club’s 70th anniversary programme for 2016-7 will run from November to April. AGM / dinner Wednesday 16 November 2016, followed by dinners on these Thursdays: 15 December 2016, 12 January 2017, 16 February 2017, 16 March 2017 and 27 April 2017.

December 17th, 2019 by admin

David Arnold, partner at Troup, Bywaters & Anders, and Stuart Thompson, senior design manager at Morgan Sindall, led the debate, which was facilitated by Ewen Rose of McGowen Rose Associates.

The dinner was marked by the presence of these finalists from the CIBSE ASHRAE Graduate of the Year award:

Ryan Rodrigues – winner

Ruth Howlett – finalist

Demitrios Constantinou – finalist

Jorge Abarca Montero – finalist

Alexandra Lindesay- Bethune – Rumford Bursary

Charity Nicholls – Rumford Bursary

2015 marks 20 years of this prestigious award, which Ewen has organised from the start.

Knowledge versus practical skills

The nature of ‘practical’ skills is changing and the next generation of building services engineers will use different tools to narrow the ‘performance gap’.

The group of finalists from the 2015 CIBSE ASHRAE Graduate of the Year awards urged their ‘more mature’ counterparts to embrace digital tools and the expertise of young engineers to deliver buildings that perform closer to their design intent.

However, the older generation lamented the lack of ‘practical’ (on-site) skills displayed by upcoming generations and urged employers to ensure graduate engineers spent more time working with other members of the supply chain or visiting construction sites to see their designs being put into practice.

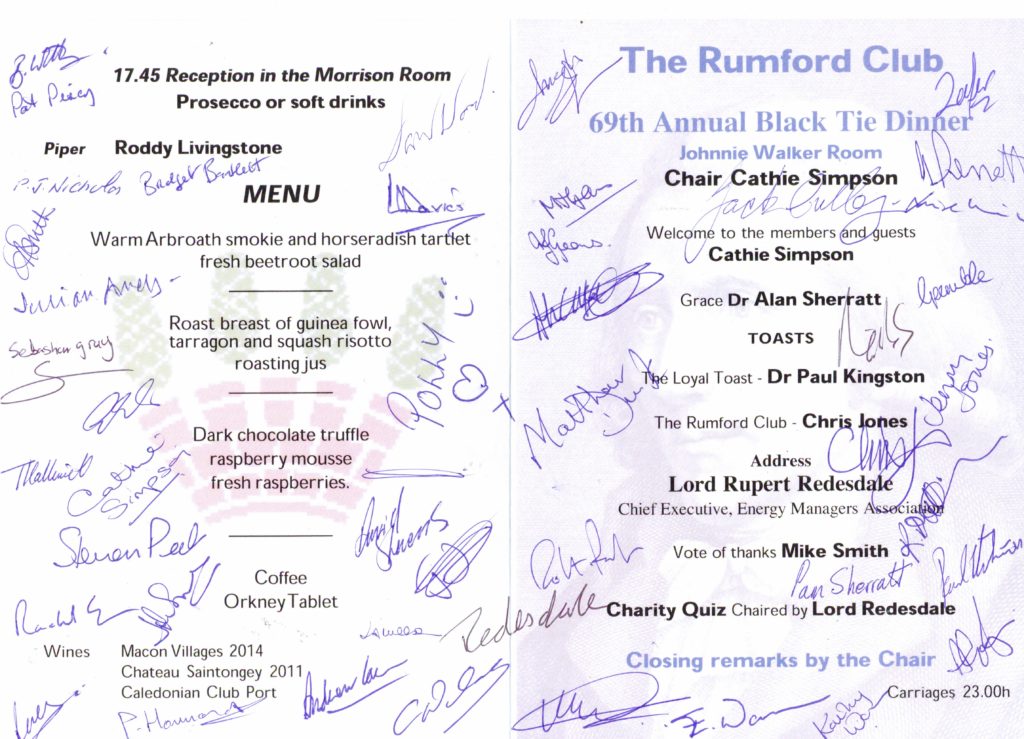

David recalled how life used to be – slide rules and “ductulators” (see image) were supplemented by a lot of practical experience, which (along with regular peer reviews) informed the engineer if their design was be likely to work well in practice.

He said that older practical skills are being replaced by new skills including the ability to use building simulation tools such as IES and 3D CAD drawing and clash detection.

Is new technology a good thing?

Some debaters argued that complex design tools leave engineers ‘wedded to technology’ and more likely to use Google to find the answer to a technical question than consult an experienced colleague. However, current CIBSE Graduate of the Year Ryan Rodrigues urged senior colleagues to stop selecting design solutions ‘because we have always done it that way’, and be more open to some of the innovative ideas produced by the next generation.

Issues with the current process

However, Stuart said innovation was being stifled by fear of litigation and regulation. He said there weren’t enough ‘feedback loops’ and because specialist design is often outsourced and split up, no one organisation owns the process, which means that no learning from the past can take place. An increase in complexity (e.g. in control systems) means that if building performance is indeed measured, we often cannot always make sense of all the data flying about.

People development

Some debaters said that what is needed is the development of and investment in right brain judgment and creativity rather than left brain analysis and calculations: this will lead to greater spatial awareness and a sense of rules of thumb rather than “hard” judgment.

Another issued that was aired is that the building service industry used to recognise its role in educating its workforce to learn technical and practical skills but training budgets have been slashed. Organisations may be reluctant that they will invest in their staff when they fear that they will simply walk away with that practical knowledge.

Change may come from an unexpected quarter. The revolution in BIM will mean that in five or so years’ time, the Government will be in a good position to understand the reasons why their building stock deviates from the design intent and will pursue those responsible.

A “year in wellies”?

Former Young Engineers’ Network (YEN) London chair Jairo Jaramillo urged CIBSE to lead a programme of practical learning and to encourage experience sharing across the supply chain similar to the ‘year in wellies’ run by the Institution of Civil Engineers as part of young engineer training.

Our next meeting

10 March meeting: “Can Integrated Performance Contracts be common-place in the UK by 2020?” Fiona Cousins (Arup) and Julia Evans (BSRIA).

December 17th, 2019 by admin

We have set up a Twitter account at https://twitter.com/rumfordclub. (Please note that one does not need a Twitter account to read Tweets).

We would encourage all Club members with Twitter accounts to follow it on Twitter and also to mention it in their Tweets where appropriate. The “handle” for such mentions is @RumfordClub.

In the course of time, as we start to Tweet (and Re-Tweet) about things that people value, and as the Club gets mentioned in Tweets by others, more and more people will follow the Club on Twitter.

Our Twitter page will enable people to get an easy snapshot of what the Club is about, how interesting the topics being discussed are and how well the Club is engaging with the wider world. Our Tweets will also be picked up by Google.

December 17th, 2019 by admin

The speaker was Cat Hirst, Head of L&D at the UK Green Building Council. The facilitator was Alex Smith (CIBSE Journal).

Originally another speaker had been engaged to give an alternative view to Cat but at the last moment he could not attend, so Cat had magnanimously jumped into the breach and provided two perspectives on the future, one more negative and the other more positive. She drew a picture of what life might be like in 2050.

This also appeared in the February issue of the CIBSE Journal – please see https://www.cibsejournal.com/general/the-road-to-salvation-what-can-engineers-do-to-slow-climate-change.

Alternative views on the future

The subsequent debate on what building services engineers could do to help steer construction to a more sustainable future was a mixture of optimism that engineers could meet the technical challenges, and uncertainty over whether innovation would be stifled by an industry wary of taking risks.

In her doomsday scenario Hirst predicted what life would be like in 2050 if the world had done nothing to combat climate change. She drew attention to the 2006 Stern Report, which suggested that countries would need to spend 1% of GDP on measures to combat the effects of climate change but said that by 2050, if nothing had been done, this could grow to 10% of GDP. She said that if nations didn’t limit to temperatures to 1.5⁰C above those in 1990, as agreed in Paris in 2015, temperatures could be 3⁰C higher by 2050.

She said that extreme flooding and drought would be experienced across the globe if nothing was done, and predicted that hundreds of millions would be displaced, ecosystems destroyed and species made extinct.

Hirst said there was an alternative brighter future if we heeded the current warnings on climate change and resource scarcity. She said emissions could be driven down by new ways of working, and the adoption of renewables and other intelligent technologies such as driverless cars.

Clients need to be educated

AECOM director Ant Wilson responded by saying that engineers had a responsibility to educate clients about building using more environmentally sensitive methods of construction. ‘I think technology can get us through, but I think we should be educating our clients, and taking it more seriously.

‘What we need to do as engineers is spend a bit more time learning how to motivate how to mentor, and how to pass on skills,’ he said.

Wilson said that if the industry didn’t do anything now it would be harder and harder to get people using fewer resources. ‘We have to do a lot of the moral things and this doesn’t always go down well,’ said Wilson.

Briony Turner, knowledge exchange manager at ARCC Network, said professional ethics made it the duty of designers to warn clients of the impact of their buildings on the environment. She said there was an ongoing debate among professions about when should designers act on their ‘knowledge’. She said she felt optimistic partly because ‘we’re having this debate and it’s not being laughed out of the room.’

A focus on cost and legal liability is hampering progress

Some of the practicing engineers in the room said that convincing companies to do the ‘right thing’ and develop more energy and resource efficient buildings could be challenging. One said: ‘Finance drives the majority of business decisions we make. What is happening today is not sustainable – it can’t continue.’

He said that change could be made by osmosis or marginal gains. ‘You need engineers putting forward better solutions but it’s about doing it through osmosis and marginal gains. I’ve sat in front of clients and said I’m going to change the world tomorrow – but when they come to sign the contract they say “I’m not going to do it. I want to sign what we had before.” You have to do in small steps rather than trying to make wholesale change.’

Cat Hirst said UKGBC members such as Ikea and the Bank of Scotland wanted to change, and were looking to engineers to lead the way.

‘All the clients we have say they want to be challenged more by the design team. The clients don’t always have the skills and the foresight to develop that brief themselves. There’s a huge opportunity to improve them.’

One engineer said that liability was holding people back. He said: ‘In any organisation you deal with corporate vision, then you get to the grey suits who need to limit their liability. It’s all about quantified liability. If you quantify the liability and it becomes something acceptable then you can change.’

Understanding cause and effect

Others said that enlightened self-interest would ensure markets delivered low-carbon buildings in time to avoid permanently damaging the climate. ‘It is common sense if you use fuel efficiently you will save money,’ said one engineer. ‘If you tell them you can save energy by doing things properly, you have got the accountant’s attention.’

For designers to have more influence over clients they have to understand the consequences of their designs on the operation of the building, according to one engineer. He said: ‘Until we as engineers bridge the gap, we’ve no chance of convincing the client, we have to understand operation, and operation have to understand design.’

Some concluding remarks

BSRIA chief executive Julia Evans said that a new generation coming to the workplace would have a significant impact. ‘Their perspective is dramatically different. I look to create an environment where they can flourish, and I look to them to be contributing to this move towards a more sustainable economy,’ she said.

The audience believed that if engineers were to make a difference they had to get their arguments across in the right way.

‘If we don’t communicate what is needed, how can we expect the client to do the right thing?’ said Ant Wilson. ‘We’ve got to do our homework. Let’s build on our presentations and persuasive natures to get people to do the right thing.’

Our next meeting

11 February 2016: “Will the performance of buildings in the future be helped or hindered by the lack of practical skills in the next generation of design engineers?” David Arnold and Stuart Thompson.

December 17th, 2019 by admin

Robin was the convenor of the report, which was launched 6 months ago. He introduced the theme by explaining its background. The Edge Commission is a multi-disciplinary voluntary group and in a good position to make recommendations for change within the Institutions as they do have a major role to play in improving the built environment. The report has not been put onto a shelf and currently there is momentum with an international collaboration on ethics, for a start. We don’t often recognise the value of our Institutions, witness the value the Chinese put on RICS.

Benita suggested the real challenge is the shortage of younger people (particularly women) adopting STEM subjects and coming into the industry and she did not see that the Institutions were making enough of a difference in this regard. She also criticised the Institutions for not sharing knowledge freely enough.

There followed a debate on how to get better at attracting people into the industry.

The meeting was marked by the presentation to Noel Gibbard, probably the Club’s oldest member at 93, of a birthday cake presented by the Club’s newest members Joseph Wu and Sebastian Gray (pictured).

Noel spoke of how Haden, the company he had worked for nearly all his working life, used to invest in a large number of apprentices. This suggested a third way forward, which would involve employers taking a more active role in attracting talent, but others argued that this is problematic in today’s climate of rock bottom prices.

Next meeting: 14 January 2016: “What might the future look like in a world of advancing technology and finite resources?” Chris Jones and Cat Hirst.